Your Neighborhood Police: 49th Precinct, The Bronx

September 19, 2018

By Edward Conlon

Millions have a picture in their minds of the 49th Precinct, even if they don't know where it is. On a map, it's sort-of box-shaped, just above the middle of the Bronx, a little to the east. Few from outside the city would recognize the names of its hard-edged, hard-working neighborhoods—Morris Park, Pelham Parkway, Allerton, Van Nest. Its low-shouldered landscape of sturdy brick one- and two-family houses, pizzerias, delis, and mom-and-pop shops has analogues in neighborhoods from Providence to Pittsburgh.

It used to be more Italian than anything else; now it's more anything else, but it's still plenty Italian—30,000 people turned out to celebrate on Morris Park Avenue when Italy won the World Cup in 2006. But anyone who has watched Raging Bull, The Wanderers, Five Corners, True Love, The Seven-Ups, Summer of Sam, or Marty has seen a version or a vision of the 49: a place where people know how to take a punch, take a chance, take a stand. It's a neighborhood that's produced more than its share of tough guys—Jake LaMotta, Stokely Carmichael—but it might surprise the audience to find out that the streets aren't so mean there, and never really were.

That might be why two local boys who became two of New York City's great storytellers set their best-known works away from home. John Patrick Shanley, an Irish immigrant's son from Van Nest, liked the way his Italian friends talked, and he made his name with a Brooklyn love story called Moonstruck ("In time you'll drop dead and I'll come to your funeral in a red dress!"). Richard Price started in his own backyard with the doo-wop era schoolyard gangs of The Wanderers, but his intimate epic of the crack wars, Clockers, takes place in the projects of New Jersey. He grew up in the projects, in Parkside Houses, but he didn't learn about the hard life at home. He once told an interviewer, "I mean, my family crest was like crossed thermometers on a field of aspirin." Still, both writers are abidingly tribal, crossing boundaries without fear, but never forgetting that the lines are still there.

Neighborhood coordination officers were introduced to the 49 in January 2018, but the precinct's commanding officer, Deputy Inspector Thomas Alps, said the adjustment wasn't difficult. "This command ran like an NCO command, even before the program rolled out. It's a very diverse, very involved community. The most diverse in the Bronx," he said. "It's almost like Queens."

The four pairs of NCOs could have been selected with precinct demographics in mind—almost half Latino, a third foreign-born—or with an eye on buddy-movie casting possibilities: there's Graham and Sanchez, the Irish guy and the Puerto Rican guy; McDowell and Hernandez, the African-American woman and the Puerto Rican guy; Varela and Cannova, the Latino woman and the Sicilian guy; Sanchez and Mujaj, the Puerto Rican woman and the Albanian guy. Got that?

Wait, it's not so simple: Graham is part Puerto Rican, Varela is half Irish, Sanchez converted to Judaism, and McDowell is also of Puerto Rican, Irish, and Blackfeet Nation heritage. Together, they speak six languages, with Hernandez adding to the home-field advantage of English-Spanish-Italian-Albanian by trading Spanish lessons for Portuguese with a Brazilian buddy at Cardinal Hayes High School, and picking up Russian to impress a woman who's now his fiancée.

Half of them were teachers of one kind or another before they became cops, and all of them spoke sincerely in civics-class terms about reaching out, connecting, and caring. They busied themselves with graffiti clean-ups and organizing "Build the Block" meetings, visiting tenants associations, merchants associations and schools. This day-to-day problem-solving in an essentially healthy community has its satisfactions—on recent visits, few went unhugged while out on patrol—but they were cops, and the point of being a cop is to be there when things go wrong. To talk to them, together and apart, you get a sense that they're slightly uneasy with how good they have it.

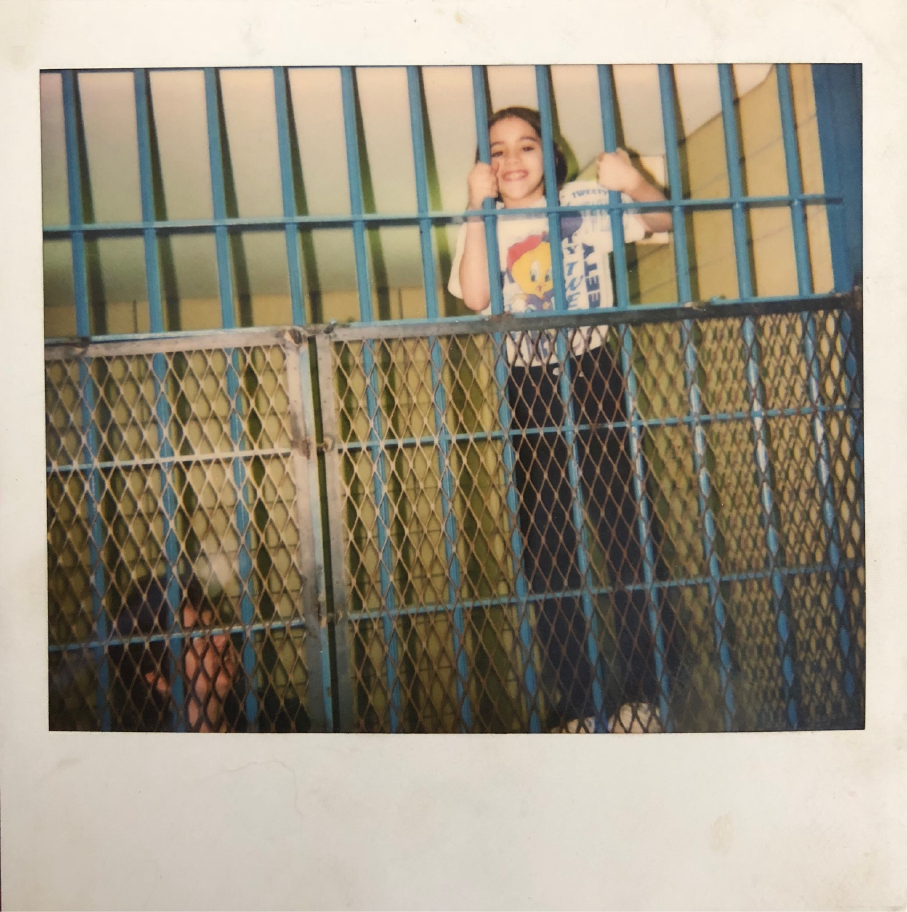

None of them are rookies. McDowell is the newest, with three years on, while Hernandez has over twelve. Several had relatives on the Job, and grew up on stories about the old days—Jay Sanchez's cousin was in the Major Case Squad in the 90s, and McDowell's uncle finished up in Mayor Bloomberg's security detail. But every cop in New York City, whether they got out of the Police Academy in 2015 or 1915, has had two distinct and contradictory messages dunned into them by the old-timers from their first day on patrol. The first was, You kids have it easy. Things were terrible in this city when I started. Followed by, You missed all the fun. Graham, who also has three years on, first heard it from his wife, who has nearly twenty. Varela wanted to be a cop since she was a kid, when her aunt, a detective in Warrants, took her to work one day.

Daisy Sanchez, a ten-year veteran, didn't have to join the police department to know how rough it was back in the day. She grew up in the South Bronx, and joined the NYPD Explorers as a teenager—a program that introduces kids in the city to careers in law enforcement. Asked if she had any police relatives, her eyes widened and she shook her head, but she sounded chipper as a candy-striper when she replied, "No, but one of my cousins was on America's Most Wanted."

*

So give me a stage

Where this bull can rage

And though I could fight

I'd much rather recite… that's entertainment.

Jake LaMotta, Raging Bull (1980)

*

There has always been a distinction between the "hard policing" of enforcement, and the "soft policing" of helping people and managing problems. Among certain old-timers, Neighborhood Policing has been dismissed as a retread of the Community Policing program of the early 90s, when there were over two thousand murders a year in the city. At the time, the "CPOP" cops were the Designated Nice Ones in each precinct, glad-handers who went to meetings while the crime-fighters suited up to hit the streets. Separating the roles didn't work. The twenty years of hard-charging police work that followed has led to astonishing drops in violence, though at a cost of a measure of social trust, particularly in poorer communities. Rebuilding that trust is at the heart of Neighborhood Policing, but it's also assumed that if that if NCOs are out shaking hands, they're going to have a better idea of which hands belong in cuffs.

On a recent visit, Varela was studying a surveillance video of a woman stumbling down the street, a grainy, gray figure against a grainy, gray background. She explained, "This woman had burns on half her body, and she managed to make her way to a Transit District, where the only word she could say was 'boyfriend.'"

For Varela, the satisfaction of being an NCO is the closer focus that comes from sticking to a specific territory. "I get to know the patterns. You don't just jump from job to job. You get to know the people, the perps. I love helping out the detective squad. I have more of a purpose as a cop now."

Varela and Cannova came in one morning and began to study the police reports that had come in over the weekend. One told of a stolen car, which was routine enough, but the keys had been taken from inside the victim's home, which bumped up the crime to burglary. More disturbingly, the suspect had placed two spray cans of paint inside the stove, which later exploded, though no one was hurt.

They examined other stolen car reports, and found that one man had been arrested twice in recent days. Hours after he was released from Central Booking for stealing a Honda in Morris Park, he tried to upgrade his ride to a Mercedes. It was a defense lawyer's car, parked beside the courthouse. His persistence was of interest, as was the fact that he lived next door to the paint-bombed home. Varela and Cannova alerted the assigned detective and an arrest was made.

Sanchez and Graham had been the Housing NCOs for a day when there was a shooting at Eastchester Houses, arising from a dispute between dog-walkers and their pit bulls.

"Your dog's a menace! Keep it on a leash!"

"Look who's talking—control your own mutt!"

The NCOs helped the detectives collect video from the scene, and the shooter was arrested. The shooter won the argument about the other man's dog, however, as it was later put down for attacking a woman. NYCHA only allows dogs that weigh less than twenty-five pounds, and pit bulls, German Shepherds, and Doberman Pinschers are prohibited altogether. Since then, Graham said, pit bull owners have taken to walking their dogs for walks on the rooftops.

"I don't have any juicy stories like that," said McDowell, though she later remembered a recent fight with a man who beat up his pregnant girlfriend in the 44th Precinct, pushing her down stairs and stealing her phone. The cop who took the report had gone to the police academy with McDowell, and he called after tracing the phone to her sector. She and Hernandez had the perp's picture and name on their phones by the time they spotted him, peeking out the window of a laundromat. When they asked who he was, he gave them a false name. When they asked the 44 to call the victim's phone, it rang in the garbage can beside him. He then proceeded to head-butt McDowell in the face, and Hernandez hurt his knee wrestling him into cuffs.

That's why days that end without a good cop story are often the best days at work. Butrint Mujaj—just call him "Trent," as he gave up on correcting the pronunciation of either of his names, long ago—liked the hectic pace of the 46th Precinct, where he started. One night, a car stop turned into a rape arrest, which almost fell apart when the victim didn't want to be a "snitch." Still, he said of the NCO spot, "To be honest, I've never been happier."

He was born in Peja, Kosovo, which used to be part of Serbia, which used to be part of Yugoslavia, and he grew up on Lydig Avenue, in the same sector he now patrols. Two of his three sisters are public high school teachers nearby, at Lehman and Evander Childs. He's at home here. When he visited Dukagjini Burek, a shop that sells traditional Balkan cheese, meat, and spinach pastries, the woman behind the counter brightened when he began speaking shqip. Several male customers eyed him warily, as did his partner, Daisy Sanchez.

"Don't be fooled," she said. "The guy lives on Popeye's fried chicken."

As McDowell and Hernandez walked around Sector Charlie, they were joined by Gene DeFrancis, a founder of the Allerton International Merchant's Association. McDowell said, "A lot of the shops here have been here for years. They have a lot of information."

DeFrancis hugged them, and the three then inspected an alley adjacent to the commercial strip, a muddy track between backyards lined with old sheds and dilapidated garages. They pointed out spots they'd cleaned up, spots that needed work. Hernandez and McDowell snapped photos of fresh graffiti with their phones, which would be attached to police reports and forwarded to Graffiti Free NYC, which paints over or cleans vandalism at no cost.

DeFrancis said he founded the merchant's association because there had been "no bridge" between the business owners and the precinct. Asked what the NCOs do for him, he replied, "Everything."

"The community's more comfortable," he continued. "Now, we have to untie their hands. You shouldn't have to be arrested fifteen or twenty times before something happens. We have some trouble spots, but it's a safe community. It's a nice feeling. It's the best feeling."

One of the trouble spots—at least one afternoon in January, when there was a gunpoint robbery —was a clothing store on Allerton Avenue called Bx Gear. The NCOs had just been assigned to Sector C when it happened, and McDowell said of the owner, Joseph Rizmany, "We check in with him. I tell him to be careful, to look at the little things, the body behaviors".

When they stopped by, Rizmany still seemed shaken by the incident. It wasn't as if he hadn't seen trouble before, as he fled Iran after the revolution of the 70s, and ran a sneaker store in East New York during the crack epidemic of the 80s and 90s. But Allerton Avenue in 2018 wasn't Pitkin Avenue in 1988, and he'd come to believe that he'd left the stick-up guys behind, much as he had the ayatollahs. He was grateful for the police attention. He hugged McDowell.

"She's too nice," he said. "She should be a nurse. She was calming me down after the robbery, she was so good."

Other residents had smaller problems, but they relied on Hernandez and McDowell no less. After the clothing store, they checked in on Coreen Gale, who routinely called them about cars blocking her driveway. When she answered the door of the brick house she shared with her twin sister, she spoke quietly, in a soft accent—Trinidad by way of Barbados, it turned out—but she was firm in her opinions of them.

"You take the time. We appreciate it. In the past, we'd call, it would take forever. These two here, they helped us a lot."

The praise embarrassed the NCOs, as cops aren't accustomed to applause for ordering drivers to move, still less for writing parking tickets. But they hadn't known until that visit that Ms. Gale had suffered from grave health problems, including a brain tumor and breast cancer. A blocked driveway represented more than a minor inconvenience to her; it was a kind of rough proof of the rudeness and coldness of the world. It also might have prevented her from getting to the hospital when she needed to get there.

Small kindnesses in hard times can mean a great deal. McDowell and Hernandez might not have much of a story to tell about their dealings with Coreen Gale, but the memory will likely remain with them longer than the aches and pains of fighting a pregnant-girlfriend-beating lowlife in a laundromat.

*

That's one of the most beautiful things I have in my life—the way my father and mother were. And my father was a real ugly man. So it doesn't matter if you look like a gorilla. You see, dogs like us, we ain't such dogs as we think we are.

Marty Piletti, Marty (1955)

*

Talking to people is what cops do, mostly. And most of the talk doesn't have to do with crime, at least as far as serious or newsworthy crime is concerned. Every contact between the police and the people they serve, confrontational or otherwise, has both a dimension of eye-to-eye intimacy and a degree of professional remove. The blue uniforms are inhabited by humans, and unless the conversation is particularly pointed and brief—"Do you know how fast you were going?" or "Police, don't move!"—the human element predominates.

Just about every cop in the country has had some sour experience with their fellow officers, whether being pulled over off-duty, or dealing with patrol officers responding to a break-in at their mother's or neighbor's house. Though conflict is inevitable in policing, those who are being policed, whether they are victims, criminals, or bystanders, know instantly whether the officer feels a sense of indifference or disdain for them. Respectful cops can't turn a bad day into a good one, but disrespectful ones can make a bad day much worse.

Talking is not a problem for Officer Giuseppe Cannova, who patrols Sector Adam with Janine Varela. Driving down Morris Park Avenue with him, he pointed out where he used to ride his bike when he was a kid, where he went to school, and how intolerably cruel Varela is to him.

"If I took off my shirt, you'd see the scars."

He's a motormouth with a Ferrari engine, fluent in three languages. Born in Partinico, Sicily, a town outside of Palermo, he came to the Bronx as a baby. He grew up speaking Italian at home, and learned Spanish from cousins who immigrated to Spain and Argentina. "At work, I maybe speak Italian once a week, Spanish every day."

Cannova goes by "Danny," having Ellis-Islanded himself like his fellow immigrant NCO Trent, née Butrint Mujaj. Daniele is his middle name, and he has no explanation as to why it stuck—plenty of Giuseppes have become Joes—any more than he can explain why he loves merengue and salsa and bachata. He says he's "culturally confused."

"He loves this neighborhood," Varela said. "He's from here. I didn't grow up far away, and I came here all the time with high school friends. But he tells me, if it was a choice between working here and working with me, he'd stick with the neighborhood."

Even so, the NCO job has been an adjustment for him. "I'm not an inside person," he said, "And there's a lot of admin. I used to be doing a lot more enforcement. And there's calls at three in the morning. If I wake up, I send it to the sector. There are a lot of calls..."

And then he stopped to take one. After he hung up, he explained that a neighborhood woman was telling him about a maybe-sort-of robbery at the liquor store across the street, in which a man took a bottle of vodka and walked out to his car, claiming he'd forgotten his wallet; the owner followed and took the vodka back. The failed shoplifter lifted his shirt, showing the handle of what looked like a gun, but he drove away. What would you call that, exactly? Theft plus force equals robbery, but the threat of force came after the property was returned. Criminal Confusion in the First Degree? Cannova told her that they'd come by to see her later.

First, Cannova and Varela stopped at the house where he grew up, on Morris Park Avenue, with his parents and grandparents, a three-story brick house with a green awning and a high stoop. In front was a concrete statue of the Virgin Mary, to the side a yard of concrete, both behind gleaming steel gates. Asked if much had changed since he moved, in the late 1990s, Cannova pointed to the statue and said that his family's statue was of Jesus. The fig tree his grandfather had planted in the yard was gone.

"Any place he found where you could plant something, he planted. With the fig tree, every branch, it'd give you maybe fifteen pieces of fruit."

But Cannova knew the reason for the steel gates. This was not the first time he'd been to his old home at work. On Halloween 2015, a driver who had neglected to take his medication for epilepsy crashed into a group of trick-or-treaters, killing three and injuring three others. It was a grisly scene, and Cannova spent hours there. A ten-year-old girl who had dressed up as a cat was among the fatalities, as was her grandfather. The driver was later arrested and charged with manslaughter. There was no doubting Cannova's sense of connection to the people here, or the place. For a moment, he didn't have anything to say. He touched the gates.

And then he was himself again. He knocked on the door and an elderly East Asian man answered. He didn't speak English, Spanish, or Italian, and the appearance of Cannova and Varela in uniform disturbed him. He left for a moment to get his middle-aged son to translate. Soon enough, Cannova set them at ease. He explained Neighborhood Policing to them, as well as his own history with the house. It soon emerged that the residents had bought it from his parents, twenty-odd years before. If they were semi-friends before, now they were practically family.

"It was a great deal!" Cannova cried out. "Remember that fight at the closing? That was my Mom!"

Though Cannova and Varela left the house with fond goodbyes from the no-longer-new owners, his reception at his next stop made it seem like they'd given him the cold shoulder. It was bingo day at the Morris Park Community Association, and the Italian ladies were playing for keeps. But their enthusiasm at the arrival of Giuseppe Cannova—there was none of this "Danny" stuff here—could be pegged somewhere above Pavarotti-level, if below that of Padre Pio. One cried out, "Giuseppe, it's the most beautiful name! It was my father's name."

As he made his rounds through the rows of fold-out tables covered with cards and tiles and dollar bills—"Is there gambling going on here?"—one after another asked if he knew this cousin, that nephew, who was on the police department. It didn't matter when he didn't.

Cannova knew many of them, such as the lady who embraced him so vehemently that she felt obliged to clarify to a visitor from headquarters, "He's not my boyfriend, he's my friend." It also became clear that he was meeting others for the first time, though the reactions of old fans and new was much the same.

"They're wonderful, wonderful people. You can always depend on them," said one, as another pressed a plastic baggie of marzipan cookies in his hand.

"Fill your mouth with sweets, they make your mouth sweet, they're special," she said, apologizing for only having one baggie left.

Cannova approached one group and asked, "Is this the Sicilian table?"

One woman nodded and hugged him, while five others bellowed: NOOOO! As he leaned in to chat, one of the naysayers rolled her eyes and confided, "We're Calabrese. She's Sicilian. That's why he likes her. She's his favorite."

Calabria is the toe of the boot, and only two miles of water separate it from Sicily, but differences remain between paesani, in the Old World and the New. Cannova later explained, "Sicilians think Calabrians are hard-headed, and Calabrians think Sicilians aren't really Italians."

Only one woman punctured the joyous mood. Asked what she thought of her neighborhood police, she raised her eyebrows and said, "I haven't seen them."

Varela briskly approached to find out what was troubling her, and a litany of complaints followed: noisy kids, people parking in front of the hydrant, dog poop. The woman scowled, "What's the matter with these people? They throw garbage!" Varela gave the woman her card as Cannova strolled to the front of the room. He picked up the microphone and said, "When I come back next week, I wanna know who won!" He proceeded to pull a numbered ping-pong ball from the spinner and called out, "O-66!"

A lady in a turquoise picked up a whistle and blew a triumphant blast, bright as reveille: Bingo! The NCOs walked out to resounding applause.

Outside, Cannova said, "One of them almost kissed me on the mouth."

*

My father says that almost the whole world is asleep. Everybody you know. Everybody you see. Everybody you talk to. He says that only a few people are awake and they live in a state of constant total amazement.

John Patrick Shanley, Joe Versus the Volcano (1990)

*

After the adoration of the bingo ladies, Cannova might have needed to have his ego taken down a peg or two, and a woman named Helen—she'd called about the sort-of robbery at the liquor store— was more than up for the job. The difference between mothers and grandmothers, Italian or otherwise, became instantly clear: one is there to stuff marzipan into your mouth; the other is there to tell you that no one in the world is ever going to give you free cookies.

When Cannova arrived, Helen barked at him, "I'm deleting your number!"

He shrugged and replied, "I've already deleted yours."

Helen went on, "I love him but he thinks he's a star. Janine's better than him. She grounds him."

They talked about the liquor store incident, which detectives were already investigating, and Helen was almost-but-not-really embarrassed by the "suspicious package" call she made to Varela.

"I thought there was a bomb on the corner. It was Election Day. There was a new bookbag, and it was placed next to the garbage can. I'm thinking, 'Should I call it in?' But they always say, 'If you see something, say something.' I called Janine, she was on vacation, but she got them here right away."

There was no bomb, and Helen might have been too slow to pick up the phone about her next observation. "There was a girl, trying the door handles of a car one day. Janine yelled at me when I didn't call."

Cops like simple, concrete problems, clear violations of the law that they can take direct action to resolve. Helen obliged them by pointing to a rusted bicycle chained to a post on the corner. "That's been here a year, maybe two. They just stole the seat."

"That we can handle, right away," Cannova said.

Helen refused to have her picture taken. "I'm not putting on makeup," she said from her yard. "Call Lefty, call Frank, call Angelo, they love being in pictures."

She did allow her son Eric to pose, as he was dressed for the occasion, on his way to the Police Academy.

After graduation, Eric would be assigned to the 52nd Precinct, just to the north. Asked if he'd be interested in becoming an NCO there, he hesitated before he replied, "I'd have to get a little more time on. The NCOs at the Five-Two took me out during field training, and I had to give talks at five different schools. Everything from what to do for a career to how to prepare for natural disasters."

It didn't need to be said that the assignment would involve constant calls from his mother, or her Five-Two equivalent on Bedford Park Boulevard or Mosholu Parkway, on-duty and off. For most cops, the struggle to maintain a separation between life and work was usually manageable; for NCOs, the border was as weak as the Maginot line.

After Helen said goodbye to her son, her voice took on a melancholy tone. "All kidding aside, they're not gonna last here," she said of the NCOs. "People are going to see their potential. They won't be here forever."

*

SISTER ALOYSIUS: You should frame something. Put it up on the blackboard. (Picking up a framed photograph.) Put the Pope up.

SISTER JAMES: That's the wrong Pope. He's deceased.

SISTER ALOYSIUS: I don't care what Pope it is. Use the glass to see behind you. The children should think you have eyes in the back of your head.

SISTER JAMES: Wouldn't that be a little frightening?

SISTER ALOYSIUS: Only to the ones who are up to no good.

John Patrick Shanley, Doubt (2004)

*

Shoplifting! That was something simple to deal with, clean and easy, without any emotional entanglements or attempted kisses almost on the mouth. At a local drug store, Varela tested the plastic barriers that protected the shelves of moisturizers and muttered, "They steal everything."

Cannova said, "I was in a meeting here a couple of weeks ago, and the alarm went off. The manager goes, 'That's one of my regulars stealing!' I ran up and made the collar."

The manager, a woman named Jacqueline, said of the NCOs, "They've been awesome. They made suggestions about lighting, lowering the shelves so you can see across the store."

Still, the pilferage was incessant. "How should I say? It's ridiculous," Jacqueline continued. "And they're professional, they're boosters. They're not stealing because they need shampoo. They're taking fifteen shampoos and selling them. Allergy medications, now they're locked up. There was my Zantac guy… body wash, personal hygiene, Motrin, Tylenol. Pediatric medicine, that's what concerns me. You don't know how it's being handled before it's sold. How long was it in the back of a 100-degree car?"

While any individual theft might appear to be petty—and are treated as such by the courts—the scale on which they occur is industrial. Jacqueline declined to specify her monthly losses, but she said that for a chain drugstore in New York City to lose $20,000 a month was not unusual. Given that there are some 400 Walgreens, Rite Aid, CVS, and Duane Reade branches within city limits, that adds up to $96 million dollars per year.

Cannova and Varela worked with the store to develop a program targeting repeat offenders. A person stopped for attempted theft would be obliged to sign an affidavit in lieu of arrest, agreeing never to enter any of the chain's locations. If they were subsequently caught inside, they were charged with Criminal Trespass; if they were caught stealing, an act that would ordinarily result in a misdemeanor count of Petit Larceny became Burglary in the Third Degree, a felony. By reviewing CCTV footage of past thefts from a variety of precinct stores, the NCOs were recently able to help detectives charge one suspect with six separate burglaries. Asked how the prosecution was proceeding, Cannova sighed and said, "This is the Bronx."

Defendants are still being treated as if they were kids who swiped candy bars instead of career thieves who worked with organized criminal networks. Jacqueline told them about a worker at another local retail outlet who dropped by to view the merchandise in her store. He smirked at a cashier and said, "We have the same stuff—only much cheaper!" The remark was what is sometimes called a "clue," in police jargon.

The NCOs consulted the NYPD Legal Bureau for guidance and mounted a sting operation. They borrowed an undercover from Narcotics, who attempted to move bottles of Pantene Pro-V Smooth and Sleek Shampoo as if they were bricks of cocaine. When the undercover offered the merchandise to another worker at the suspected fencing location, he was told, "Come back in a few hours, the boss handles this stuff."

But Cannova underestimated his opponents. He was at the drug store in plainclothes when the undercover made a second attempt to sell his wares. His best guess was that he was made by a spotter, and the message was relayed to the fence. The undercover later told him that they were about to do business when the boss got a phone call, and the deal was suddenly off. He was sent packing, along with his ill-gotten shampoo.

"They're impressive, our thieves," Jacqueline acknowledged, before adding with a lock-jawed resolve, "But we're better."

Her aversion to shoplifting apparently drew on more than professional obligation. Unprompted, she volunteered, "When I was a kid, I stole a pair of earrings. Lion King earrings," she half-shuddered, half-laughed as she finished. "My dad found out. He took me back to the store, and he had a cop buddy yell at me. That was it for me."

*

It's a shame to see kids beatin' each other's brains out, especially when there's no financial advantage.

Richard Price, The Wanderers (1974)

*

Al D'Angelo knows everything anyone needs to know about the neighborhood. Though he grew up in the South Bronx, he moved to Morris Park in 1979, and he lives there with his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson. He's retired from a career as a teacher and principal in Catholic elementary schools, and is a past president of the Morris Park Community Association and incoming chair of Community Board 11.

As a sideline, he has served on the boards of Cardinal Spellman High School, Aquinas High School, the Jacobi Medical Center and Einstein College of Medicine, and too many others to mention. He volunteers with the enthusiasm of a Labrador Retriever chasing sticks. It had almost become a bad habit for him. When his grandson joined him on the stoop, he whispered, "Don't tell Grandma about the Community Board!"

Asked about Cannova and Varela, he reflected for a moment before he replied, "Eh."

And then he laughed. "It's worked out so great. It's one of the better things the City's done. I don't want to give them a swelled head, but they're great."

Nodding to Varela, he said, "She keeps his feet on the ground. Our complaints here are mostly quality-of-life things. We had this one kid, doing graffiti all over the place. People's houses, cars. They coordinated with the City Wide Vandal Squad and got the kid. He cried this time. We haven't seen another thing with his name on it. We want the sector to be smaller. But we want to keep these two.

"Actually, my concern is that they're overburdened. They return every call. I tell people, 'Call if it's something they can deal with.' Not, 'There's a cat on my porch.'"

Cannova nodded with vigor, adding, "Or, 'The neighbor's leaves are on my lawn.' On my day off, I'm on the phone for an hour." His voice grew shrill as he recalled a recent conversation: "'There's fireworks going off, and it's scaring my cats! It's going BOOM BOOM BOOM! And my cat's going up in the air! And my cat has a heart condition!'"

He shook his head. "I don't know who's crazier, her for calling, or me for answering."

D'Angelo lived on a maple-lined block of two-story brick houses with tidy yards fenced with wrought iron and white picket. Many homes displayed American flags; a few houses down from the D'Angelos, there was an elaborate shrine to the Virgin Mary in a circular steel frame surrounded by pink and white flowers. It would have looked much the same forty years ago, when the block was almost all Italian, aside from a neon sign atop the frame that said, "Đức Mẹ La Vang,"—Our Lady of Lavang, after a Vietnamese village that has become emblematic of Catholicism in that country.

"As long as you take care of your house, take care of your kids, you're welcome," D'Angelo said. Not too long ago, he met a man named Yahay Obeid, who is the director of outreach for the local mosque. Obeid emigrated from Yemen when he was eight, and he's an official at the Federal Aviation Administration. D'Angelo invited him to give a talk at the Morris Park Community Association. "I said, 'All we know about Islam is from TV and the papers, and it's all about terrorism. Do you want to give a presentation for us?'"

Obeid took him up on the offer, choosing an Italian woman who had converted to Islam as a speaker. He has since become a member of Community Board 11.

Ramadan began in mid-May, and cars were crowding around the mosque on Rhinelander Avenue for evening prayers. D'Angelo laughed about how they dealt with the situation.

"They tried so hard to be good neighbors they were calling the meter maids on themselves! I said, 'You don't have to do that!'"

Cannova and Varela arranged to spend sundowns at the mosque to manage things. Cannova wound up getting an invitation to speak at the Yemeni Merchant's Association, and his talk was livestreamed to thousands of people around the world. Neighborhood Policing had gone international! It's possible Varela suspected that her partner needed a bigger hat for a while, but she knew how to manage him.

At that moment, a visitor from headquarters might have been forgiven for thinking that the government hadn't done such a good job since the Marshall Plan. Every empty platitude about diversity and community had been jury-rigged and hot-wired and bulldogged into a good and real thing. It was an afternoon of spotless sunshine at the end of May, after an endless winter that seemed to keep shaking itself off like a cold, wet dog. Who couldn't love this? Who couldn't believe in it?

Just then, the wary lady from bingo pushed her cart down the block. She watched the police but said nothing as she passed by. She was from the neighborhood, and she'd heard it all before.

She'd have to wait and see.