Department of City Planning311

Department of City Planning311 Search all NYC.gov websites

Search all NYC.gov websites

Press Releases

For Immediate Release

October 4, 2019

Contacts:

Rachaele Raynoff, Joe Marvilli – press@planning.nyc.gov (212) 720-3471

DCP Director Marisa Lago’s Remarks at Today’s 163rd CityLaw Breakfast at New York Law School, as Prepared for Delivery:

Good morning. A quick introduction – and as some of you may know – I wear two hats in my current role: I am both Director of the Department of City Planning (DCP) and Chair of the City Planning Commission (CPC). Today, I will be speaking wearing my DCP hat.

I am a New York City (NYC) government junkie and of government in general.

Before this job, my most recent stint was in the Obama administration. I had a post at the United States (U.S.) Department of the Treasury – Assistant Secretary for International Markets and Development - which means that I was in Beijing much more frequently than I was in NYC.

And when I returned to NYC, I found a very changed city.

At DCP, we love facts, figures and statistics. So, I am going to give you a few snapshot statistics that give a sense of where we are as a city today.

We are at about 8.4 million people, and we are the only older U.S. city that has surpassed its 1970s-era population peak.

We also have 4.5 million jobs – that is an all-time high.

Between 2010 and 2018, we added nearly 800,000 jobs. That is more jobs than in the entire City of Boston.

This incredible growth poses opportunities – but also challenges.

It is important to remember that despite the growth in population in NYC, we still have the same 303 square miles of land. So, to grow sustainably and equitably, we have to build more housing – and especially affordable housing. And we also have to create what I call “space for jobs.”

While sustainable, equitable growth is my principal topic, I cannot at this point, eight months out from the Census, not start my remarks without talking about its importance.

The Census is enshrined in our Constitution. We rely on an accurate Census to assure that we get fair representation in the House of Representatives.

We also rely on the Census for an equitable distribution of federal dollars - dollars that are used for everything from school lunch programs in low-income neighborhoods to fixing bridges.

And, at DCP, we rely on the Census for its rich demographic data about our residents.

After all, how can you plan for a city if you do not understand its population?

The federal government’s proposal to add a citizenship question to the 2020 Census was a direct threat to a full count in our immigrant rich city – and a lot of damage has already been done simply by proposing the idea.

We have now defeated the citizenship question. A huge “thank you” to our Supreme Court.

But now, it is important that we get the word out to all communities, and most especially minority and immigrant communities -- because they are the ones that historically are undercounted -- that it is essential to be counted.

We are going to have to work especially hard to achieve a full count in New York Census because of the anti-immigrant actions and rhetoric coming out of Washington.

I will give you some statistics that illustrate the magnitude of the challenge in NYC.

37 percent of New Yorkers are foreign-born. If you go to the Borough of Queens, that rises to over 50%.

60% of us have at least one foreign-born parent.

One in seven New Yorkers lives in a household with a non-citizen.

DCP is home to NYC’s world-class demographers. Last year, they found 123,000 residential addresses that had been missed on the federal Census Bureau’s official address list.

That alone means that 300,000 New Yorkers – more people than entire city of Cincinnati – will now receive a Census form and have the chance to be counted.

DCP has many allies in our quest for the holy grail of a full Census count. It starts with the NYC 2020 Census Office and extends to myriad outside organizations: the Association for a Better New York, countless ethnic and religious groups, and media outlets. I thank them all for their support. This has to be a city-wide campaign.

And I urge everyone in this room to get involved by filling out your Census form when it arrives in March 2020. But also by spreading the word – in your child’s school, in your workplace, in your house of worship, at your block association – that every New Yorker benefits themselves and their city by filling out the Census form.

I will spend the next portion of my remarks focusing on a few ways in which DCP helps our city grow sustainably and equitably.

One way we do this is by making sure that the city’s Zoning Resolution facilitates the production of housing – especially affordable housing – and facilitates the creation of space for jobs. Jobs in classic sectors like finance, the arts, construction, and traditional manufacturing, but also jobs with different space needs in the so-called “new economy.”

As-of-right development is the workhorse of producing both housing and space for jobs. For non-zoning geeks, as-of-right development means that a property owner whose proposed building complies with the requirements of our admittedly complex Zoning Resolution can go directly to NYC’s Department of Buildings (DOB), without requiring approval from either the CPC or the City Council.

NYC’s as-of-right statistics are impressive.

Over 80 percent of new housing produced since 2010 has been built as‐of‐right. Without this development, approximately 300,000 New Yorkers – an entire Pittsburg – would not have the homes in which they live today.

If we were like San Francisco, where practically every development project had to go through discretionary project review, we would be producing far less housing, thus becoming increasingly unaffordable.

Another way in which DCP fosters sustainable, equitable growth is by engaging in comprehensive, community-informed, fact-based planning. This planning can lead to a neighborhood rezoning that increases the allowable residential density in transit-rich neighborhoods, while reducing the need to provide parking, which jacks up the price of construction.

These neighborhood rezonings are accompanied by significant capital investments -- in parks, in schools, in streets, and in other areas that have been identified by the community.

Importantly, since 2016, new housing that results from these residential upzonings has to provide a minimum of 20% permanently affordable housing. This is the core of MIH -- Mandatory Inclusionary Housing -- which is enshrined in the Zoning Resolution.

Unfortunately, one sometimes hears that DCP only rezones low-income neighborhoods. This paints a false picture of where housing development is occurring, and where we are creating affordable housing opportunities.

Since 2015, fully 36% of new housing construction has occurred in the 25% of neighborhoods with the highest median incomes.

And about one-third of the new affordable housing that has been completed was built in these same high-income neighborhoods.

Let me give just one upcoming example. There is a single block in Chelsea, just south of Hudson Yards. There, two owners of large, nearly vacant industrially-zoned land have received CPC and City Council approval to construct two large buildings. These buildings will contain about 950 housing units – including 300 permanently affordable housing units. That is a lot of affordable housing that is being created in a very high-income neighborhood on just one block, and without any discretionary NYC subsidy.

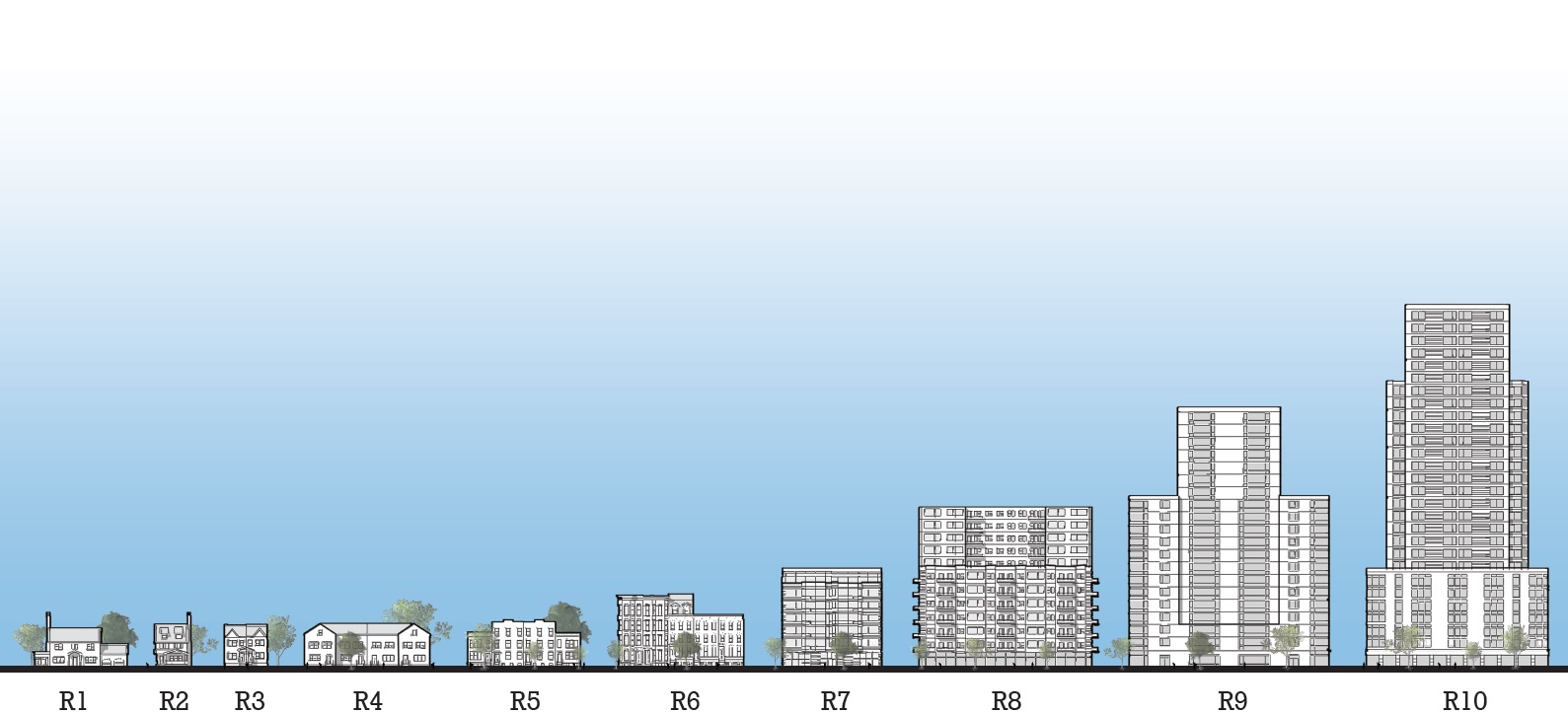

To grow sustainably and equitably, we need to build housing of all different types. And, fortunately, our Zoning Resolution allows this – from single-family homes in areas that are far from transit, to six-story multifamily buildings, to tall buildings in transit-rich neighborhoods.

In a city as space-constrained as we are, and as transit-rich as we are, tall, dense buildings are the backbone of new housing construction. Intuitively, we thought that this was the case, and our research has shown it to be true.

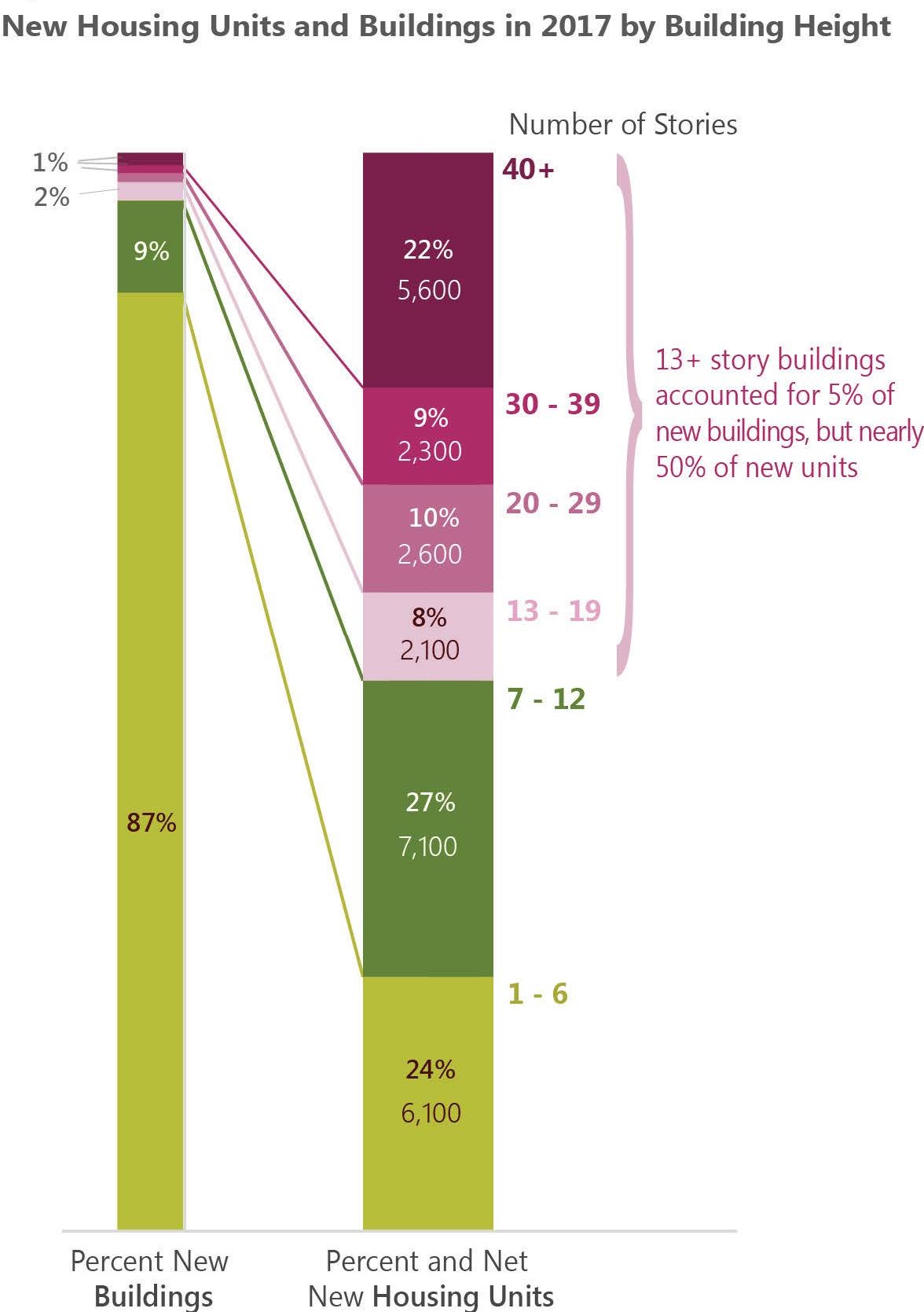

We looked at all of the residential buildings that were completed in NYC in 2017. New housing units in one- to six-story buildings represented 87% of the new buildings, but only 24% of new units.

About 50% of the housing units were in buildings of 13 stories or more. All of these mid-rise buildings were in transit-rich neighborhoods.

Here is the most surprising statistic of all: the 1% of new residential buildings completed in 2017 that were 40 or more stories – that is just 18 buildings, this 1% accounted for 22% of new housing units.

I will move now to LIC in Queens and Downtown Brooklyn. Because they are prime examples of how well-planned rezonings help our ever-changing city to evolve over time. Each of these neighborhoods was rezoned more than 15 years ago, laying the groundwork for vibrant new “live/work/play” neighborhoods. As expert DCP’s planners are, we do not have a crystal ball. So sometimes the evolution of rezoned neighborhood happens in a different sequence than anticipated.

Back in the early 2000s, when LIC and Downtown Brooklyn were first rezoned, the expectation was that back-office jobs would move from Manhattan to these lower-cost locations.

As we know now, the economy evolved, and many back-office jobs were eliminated through automation, and others moved to other regions of the country or globe.

So, instead of housing back-office functions, these neighborhoods today are at the forefront of the nation’s high-tech and creative economy – and this is occurring because our zoning was flexible enough to let housing lead the way.

Let’s take a slightly deeper dive into Downtown Brooklyn. Here, new housing has attracted a highly talented workforce, which in turn has attracted businesses and jobs.

In 2004, there were fewer than 1,000 homes in Downtown Brooklyn. Today, there are 12,000 homes, 2,000 of which are affordable. That means that today there are more affordable homes in Downtown Brooklyn than there were total homes in 2004.

As an aside – and because we want all these smart college students to stay when they graduate: did you know that Downtown Brooklyn has 11 institutions of higher learning with 63,000 students? That is more students than in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Employers have taken note of this talent pool. From 2001 to 2015, private sector jobs in Downtown Brooklyn grew from 48,000 to 58,000. That is 20% job growth, despite two recessions.

I have been pleased recently to see two new 100% commercial buildings proposed in Downtown Brooklyn, further fulfilling the promise of the 2004 rezoning.

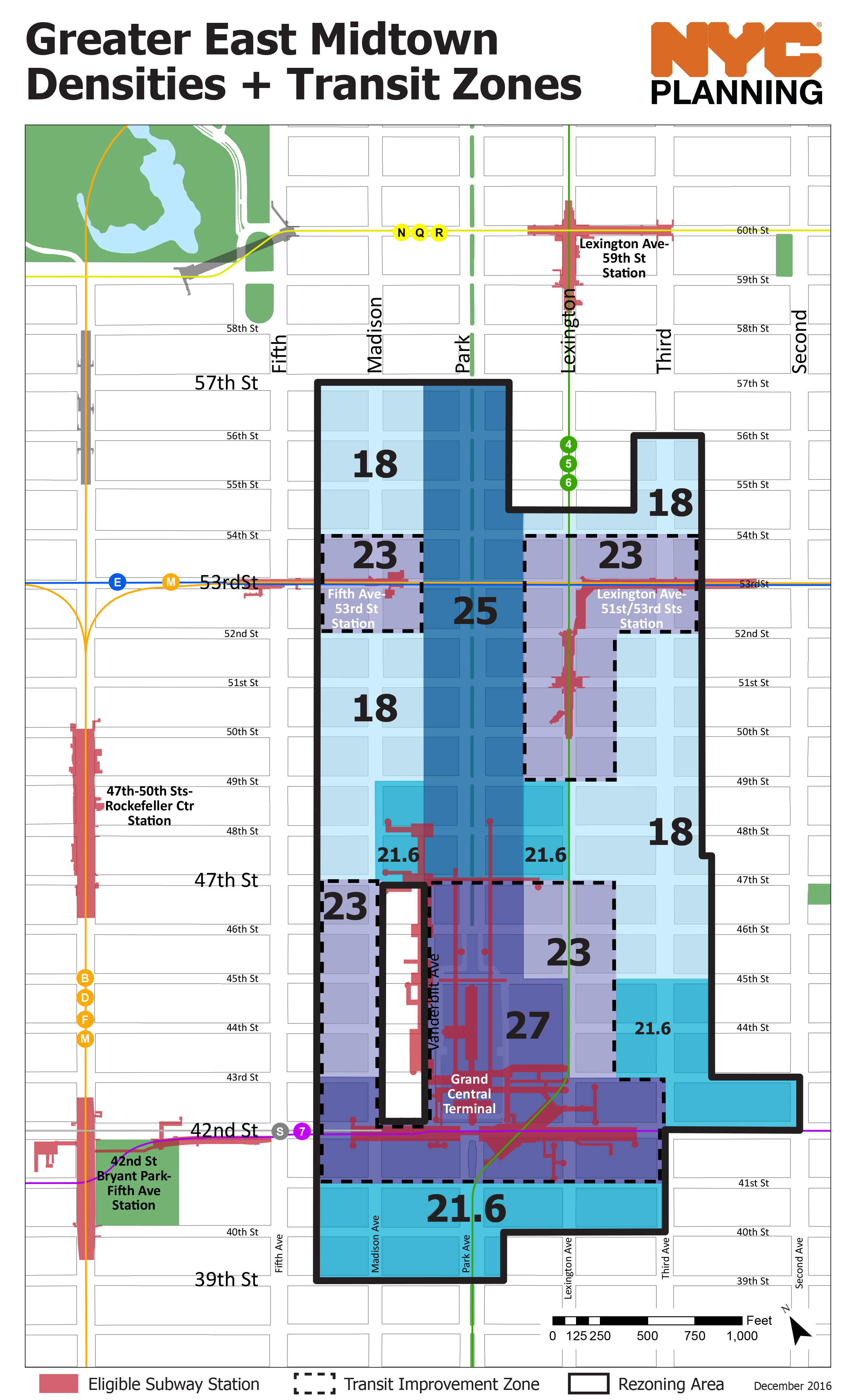

I am now going to pivot more explicitly to zoning for jobs. I am going to be talking about Greater East Midtown. It is a little bit presumptuous of me to be speaking about this in a room that contains Edith Hsu-Chen, who heads our Manhattan office, Anita Laremont, our executive director, and Carl Weisbrod, my predecessor, because they are the ones who drove through the rezoning and are responsible for the successes that I am going to share with you.

Years of sound planning led to a very significant upzoning of the area around Grand Central. In a nutshell, this rezoning allowed property owners to redevelop their out-of-date office buildings – which are on average 70 years old.

These 70-odd blocks are in the middle of NYC’s – and, I would dare say, the nation’s and the globe’s – premiere business district. The rezoning was done as part of a well-balanced plan. This plan stipulates that sites that sit atop the area’s numerous subway stations can only take advantage of the rezoning if they provide pre-determined upgrades to the subway stations at the land owner’s expense. That already is a win-win.

But, the East Midtown rezoning went further. It allows East Midtown’s numerous beloved landmarked buildings to sell their unused development rights to the owners of these outdated office buildings, who want to take advantage of the more liberal zoning. But a portion of the sales proceeds has to go to improvements to the sidewalks, streets, green spaces and subway stations in the neighborhood. That is a win-win-win.

I could go on and on about this amazingly balanced and effective plan. But I will conclude by noting that, while the East Midtown rezoning is less than two years old, already five landowners are taking advantage of the updated zoning, creating space for jobs and providing hundreds of millions of dollars for subway and streetscape improvements.

Sticking with the topic of space for jobs, sometimes the best thing that NYC government can do is to get outdated, overly prescriptive zoning out of the way of businesses that want to construct space for jobs.

We are keenly focused on updating NYC’s 1960s-era zoning for manufacturing districts outside of Manhattan that have good public transit.

Our current zoning was established at a time when America was in love with automobiles. It envisions very low-density, one-story manufacturing plants, surrounded by a sea of parking.

A thriving manufacturing business that wants to expand vertically is likely to find itself restricted by an allowable density that is too low, and parking requirements that are too high.

So, we are looking at opportunities to: markedly reduce parking requirements in transit-rich manufacturing districts, provide a wider array of permitted densities to allow manufacturing businesses to grow vertically, and give more flexibility to envelopes of buildings.

By way of example, with the 1960s-era zoning, the envelopes that are provided make it practically impossible to build today the tall, dense lofts of the Garment Center.

Or even the shorter, but still dense, beloved lofts in Dumbo or LIC. We believe that the chunky, funky NYC loft – which has housed our city’s ever-evolving businesses for well over a century – should be allowed to be constructed as-of-right in our commercial and manufacturing districts with good mass transit.

An important example of the need to update antiquated zoning can be found just three miles north of New York Law School in the Garment Center.

The Garment Center’s manufacturing zoning was put in place in 1961, when the area was a thriving hub of garment industry jobs. At just about this time though, global forces led to a drastic decline in manufacturing – in the U.S., across the city and very notably in the Garment Center.

There was a well-intentioned effort in 1980s to deploy zoning to try to keep the Garment Center jobs in the city by requiring that, for every square foot of space converted to a non-manufacturing use (such as office space) an equivalent amount of space had to be permanently dedicated to manufacturing.

Powerful as zoning is, it cannot stop the tide of a changing global economy. So, rather than keeping manufacturing jobs in the Garment Center, the overly prescriptive zoning only served to keep space empty – and empty buildings do not provide jobs, and owners of largely empty buildings are unlikely to engage in renovating their aging buildings. And that is exactly what happened in the Garment Center. As the rest of Midtown thrived, the Garment Center’s upper floors were largely empty and the streets disturbingly quiet.

I am pleased that in 2018, NYC successfully rezoned the Garment Center to allow a full range of office, retail – and, yes, – manufacturing uses. This change will spur reinvestment in these beautiful loft buildings to house the jobs of today – whether workspace for the TAMI (tech, arts, media and information) sectors, office space for non-profit organizations, or manufacturing and showroom space for the garment industry.

I use the Garment Center as an example of how overly prescriptive zoning can thwart job creation in a changing economy. But it is yet another example of how adoption of more flexible zoning – which allows building owners and businesses alike to adapt to a changing world – is key to the city’s economy.

Now let’s look at how DCP plans through another lens. We can only continue to thrive if resiliency is front of mind in our planning and building.

We are a city with a magnificent and diverse 520-mile waterfront – one that we have rediscovered in recent decades.

To give a sense of the vastness of our waterfront: Los Angeles, San Diego and Anchorage each has more land area than NYC, but we have more waterfront than these three cities combined. In fact, you can take any combination of three major U.S. cities and we have more waterfront than the total of these three other cities. This extensive coastline provides us with a wealth of water-dependent jobs and residential neighborhoods, as well as magnificent recreational amenities.

But Superstorm Sandy – seven years ago this month – was a brutal reminder that, as a coastal city, we face increasing risks from climate change.

NYC has done a lot to address those risks – and we are focused on the very real challenges of providing coastal protection in a dense urban environment where practically every square inch of land is already spoken for.

There are important large infrastructure projects, including in the Rockaways, on the East Coast of Staten Island, and on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, that include building coastal protection infrastructure.

But land use and zoning are also part of the NYC’s resiliency strategy.

And that is why DCP is pursuing Zoning for Coastal Flood Resiliency.

It involves changing land use and zoning throughout the floodplain.

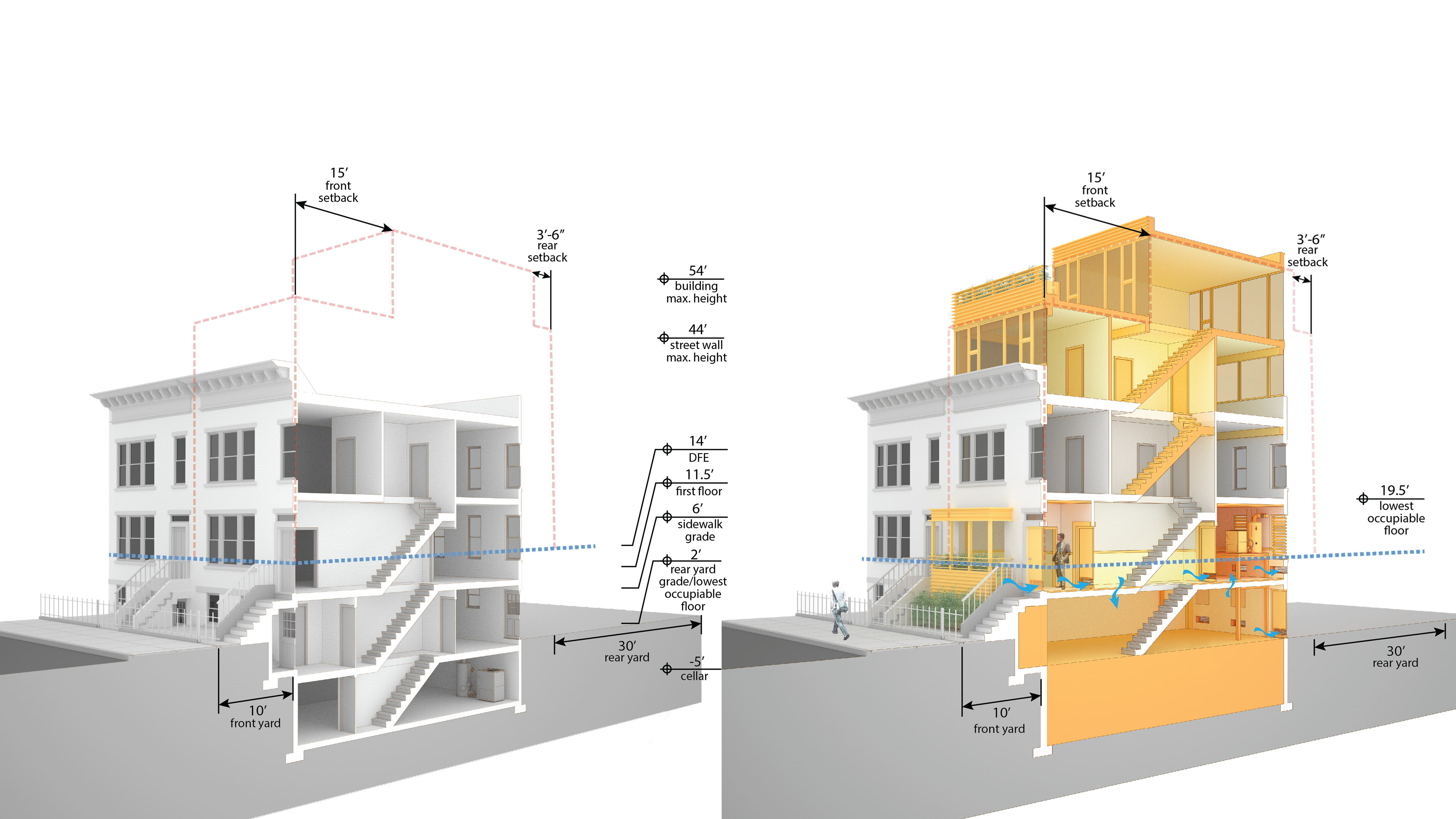

Currently, homeowners and small business owners who are interested in mitigating flood risk by elevating their buildings and mechanical equipment can run into complicated regulatory barriers, turning even a small retrofit into a major challenge.

Recognizing this, post-Sandy, the CPC put into place temporary, emergency zoning regulations in the floodplain. They removed zoning hurdles and encouraged flood-resilient building construction and reconstruction.

We have now had seven years of experience living with these temporary regulations. And we have learned a ton by reaching out extensively to neighborhood residents in the city’s varied types of flood-prone areas.

Last spring, we issued our preliminary recommendations for a citywide zoning text change, which we are calling Zoning for Coastal Flood Resiliency.

We expect the formal zoning text amendment to enter ULURP – the formal land use public review process – early next year.

Let me give a few examples of the types of changes we are proposing.

A family on Staten Island, on the Rockaways, or Howard Beach, may want to raise their home to protect against climate change, but if they do, they lose their basement, which may have been used for recreation. They lose the space because of maximum roof height restrictions in our zoning rules. Or, they want to move the boiler out of the basement – and so out of harm’s way in a storm – but doing that also means they lose living space in their home – space which is at a premium in NYC!

The proposed zoning changes would allow these small bits of additional height for new construction and retrofitting of homes. If adopted, these clear as-of-right rules will help buildings throughout the city take strides toward a safer, more resilient future.

I will end by touching briefly on some recent examples of the type of deep dive, research-based analysis and planning for which DCP is well-known.

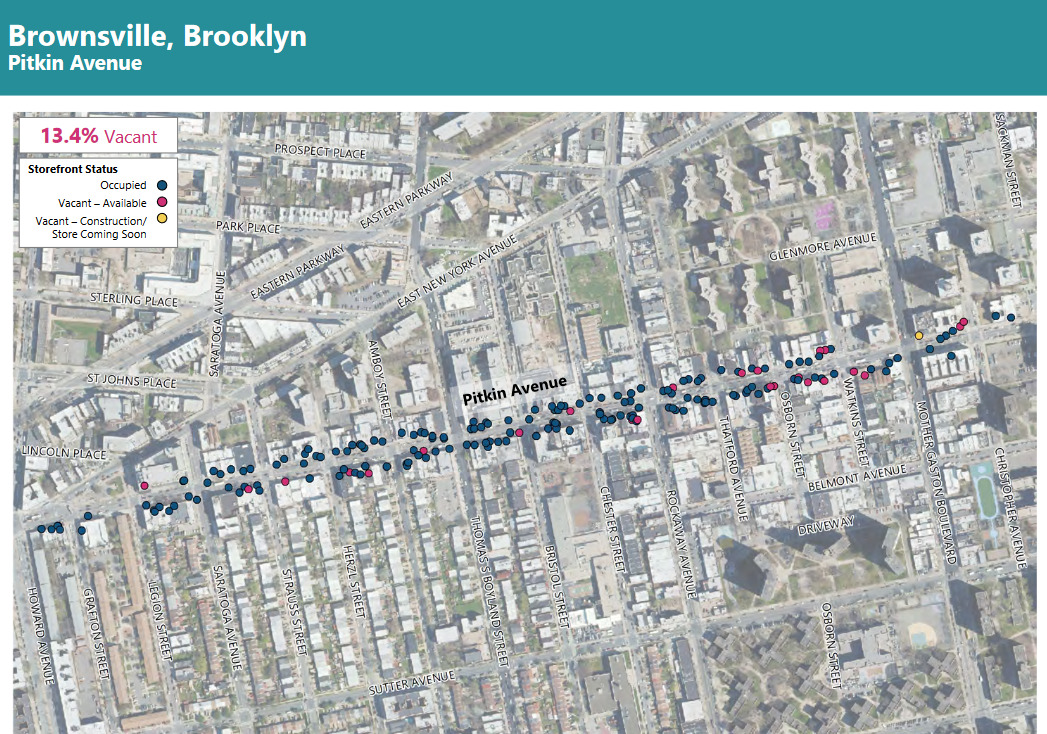

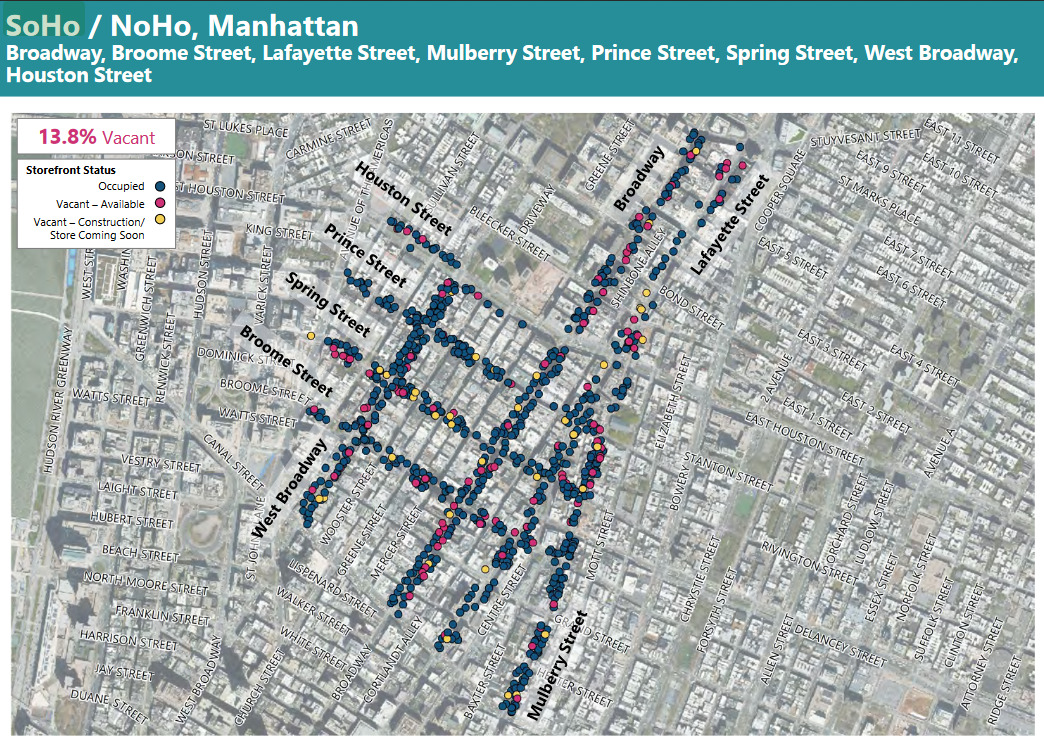

This summer, DCP released a groundbreaking study entitled Assessing Storefront Vacancy in New York City.

It offers a detailed exploration of recent retail trends and storefront vacancies in NYC against the backdrop of shifting technology, economic forces and changing consumer preferences.

It is the most data-driven, in-depth look at these issues to date. We surveyed over 10,000 stores in 24 pedestrian-oriented shopping corridors across the five boroughs.

Some of the study’s takeaways are already widely known. It is unremarkable to say that the retail industry is changing rapidly across NYC and the country.

But, other of our findings run contrary to public perception. We found that vacancy rates are not uniformly high across the city.

Rather, they vary from neighborhood to neighborhood, and even from street to street within a neighborhood. And, vacancy rates cannot be pinned solely on landlords holding out for more rent.

The reasons for these vacancies vary neighborhood by neighborhood. Let me give just one example. Both SoHo and NoHo and Brownsville have the same 13% vacancy rates. But the reasons for the vacancies are far different.

In SoHo and NoHo, a rent bubble encouraged owners to keep space offline and very prescriptive zoning limited the types of businesses that were able to locate there. Indeed, the zoning required some of the space to lie fallow.

On Pitkin Avenue in Brownsville, the challenges are very different. There, our report found that a weaker retail market, a lack of anchor stores and limited subway access hurt occupancy rates.

There are other factors at play, such as the rise of e-commerce and consumer preference shifting to experiential retail.

Our main takeaways from our in-depth study is that there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to retail vacancy fixes in NYC.

This research will inform our neighborhood planning work, and the work of other researchers and policy makers who may have other non-zoning tools to address the needs of small business.

I will end by highlighting DCP’s Regional Planning work.

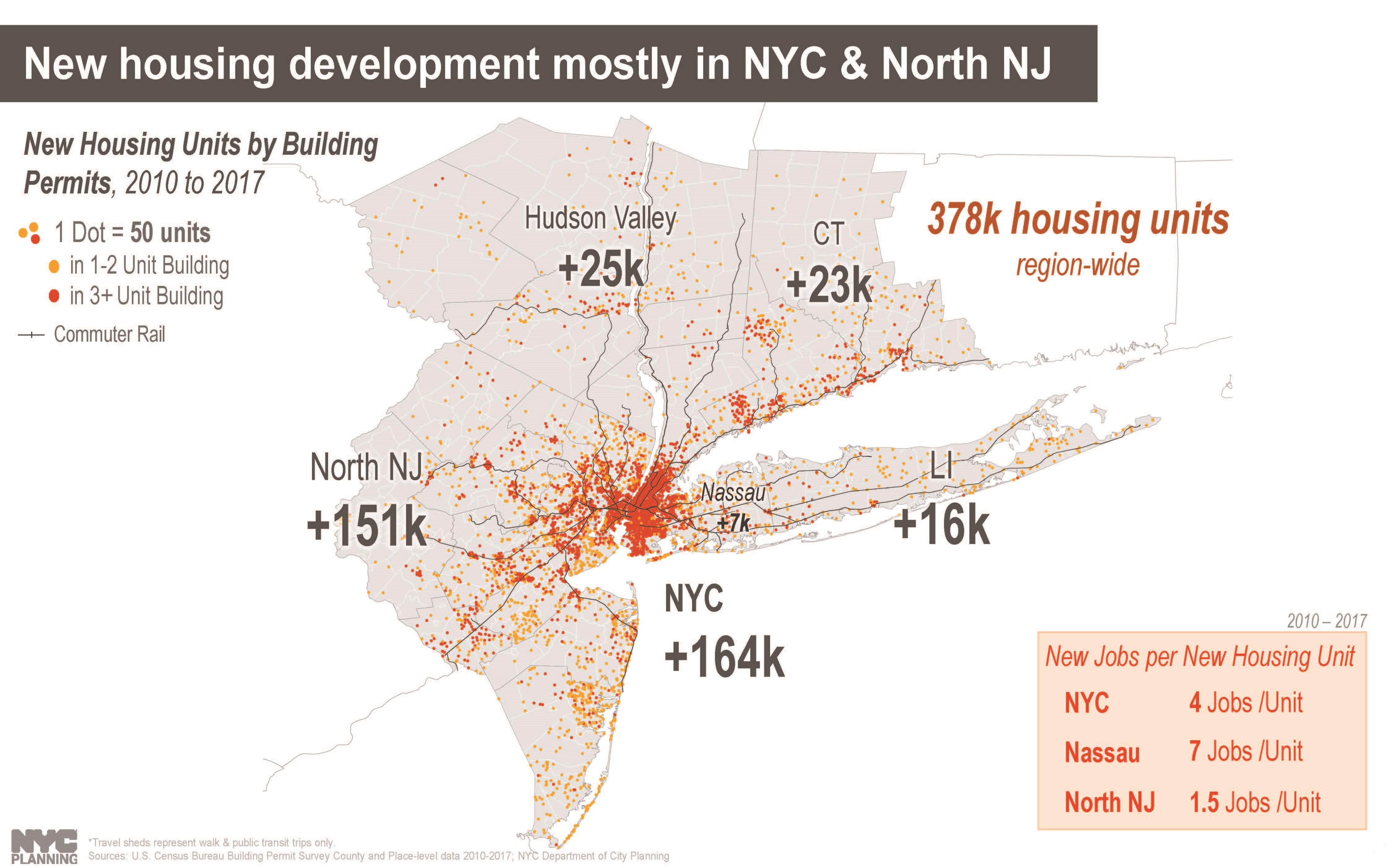

While our Regional Planning Office is only three years old, it is already changing how we – and governments throughout our 31-county region – are thinking about our interconnectedness, and how we have to factor this interconnectedness into our long-term planning.

In NYC, we understand that housing affordability is a major challenge – but we also have to be aware that the region as a whole is falling woefully behind on housing production.

Historically, the suburbs to our north and east have been affordable alternatives to city living. But, for years, these jurisdictions have allowed extremely restrictive zoning to curtail their housing production.

While suburbs in northern New Jersey are producing housing, this region lacks the same level of commuting infrastructure to support long-term growth.

We believe that, to remain a prosperous and affordable region, we must do more to connect our jobs, housing and transportation planning regionally.

We are investing in building our data-driven analysis of the region and forging working relationships with our counterparts in municipal and state governments. Our goal is to bring regional knowledge to bear in our – and other governments’ – local planning efforts.

We have been heartened by how county executives and mayors in our region have welcomed the DCP’s Geography of Jobs report and look forward to deepening our planning ties with our neighbors.

And with that, I will gladly take your questions.