Department of City Planning311

Department of City Planning311 Search all NYC.gov websites

Search all NYC.gov websites

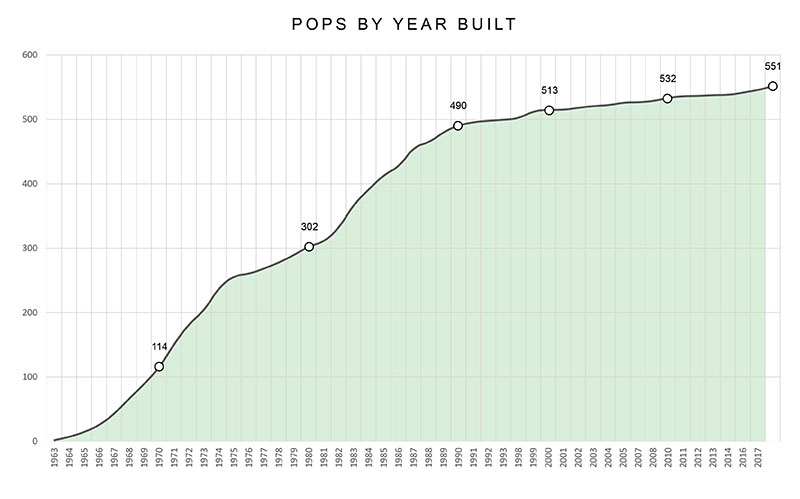

This page recalls the history of POPS in New York City, dating back to 1961, and detailed evolution of these spaces. Important milestones and phases include the following. Please read on to learn more!

- 1961: Inauguration of the Program

- 1968-1975: New types of spaces

- 1975-1977: Major improvements to plaza standards

- 1980-1990: Incremental changes

- 2000: Data collection and book publication

- 2007-2009: Ushering in a new era of plazas

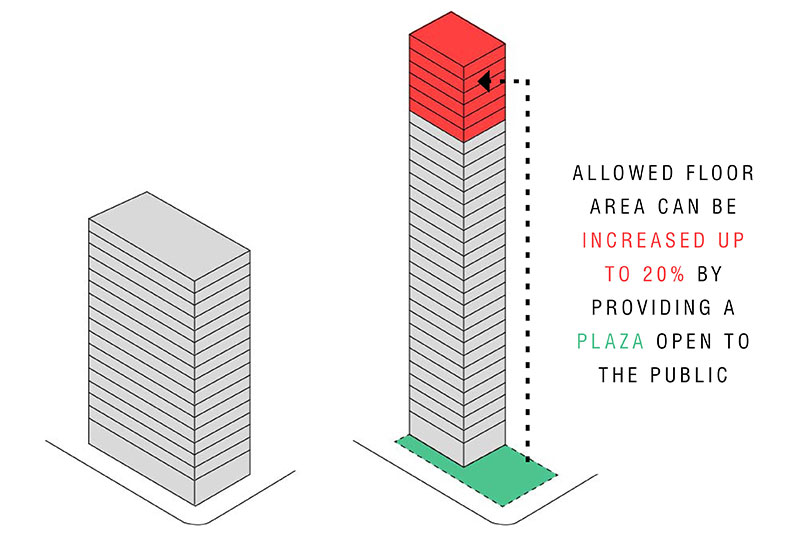

The 1961 Zoning Resolution inaugurated the POPS Program in New York City. It encouraged private developers to provide publicly accessible spaces, specifically plazas and arcades, on private property in exchange for bonus floor area in certain high-density districts. It was one of the earliest forms of “incentive zoning.” Inspired by developments such as the Seagram Building in Midtown Manhattan, the intent was to bring light, air, and more usable open space to our city streets, at a time when many bulky buildings and skyscrapers were being constructed.

The Zoning Resolution prescribed modest dimensional and design requirements for these spaces, and required them to be accessible at all times. The original standards did not require any amenities we expect in public spaces today, such as seating, lighting, and trees, and rather only permitted elements such as flagpoles, driveways, and garage entrances . The standards also set a maximum bonus cap of 20 percent of the maximum permitted floor area for any lot. The bonuses were “as-of-right”, meaning that developers only needed to demonstrate compliance with the zoning requirements and floor area computations at the Department of Buildings and did not need to seek Department of City Planning review.

The bonus was an immensely popular incentive for developers; it was fairly low cost and created additional space and value to a building. By 1996, when the regulation standards were updated, 167 plazas and 87 arcades had been built. Among these are many of the large open spaces pedestrians encounter today in Midtown Manhattan and the Financial District. This plaza bonus remained in effect until 1996.

Because the plaza bonus had proven to be a powerful incentive, the City, in 1968, began adopting additional types of bonus-generating public spaces into the Zoning Resolution. Each of these had its own set of standards and bonus ratios and required review by the City Planning Commission. These included elevated and sunken plazas, through block arcades; covered pedestrian spaces; and open-air concourses.

Additional POPS were built as required by various special purpose zoning districts, as part of a big-picture urban design vision for a certain area of the city.

Further, some POPS were built by building owners in exchange for waivers from existing zoning rules from either the City Planning Commission or Board of Standards and Appeals. These waivers typically were to allow for floor area greater than the base amount, or for modifications to height, bulk, or setback rules.

Over time, it became apparent that there was a need to improve plaza standards. Plazas built under the 1961 standards brought light and air to the street level as intended, but a vast majority did not provide usable public open space. That was because the standards did not require seating, lighting, or trees, and rather only permitted elements like flagpoles, driveways, and garage entrances . The result: underused open spaces.

In 1975, with the benefit of hindsight and encouraged by research studies produced by William H. Whyte, the Department adopted the “Urban Open Space” amendment in 1975, which significantly improved the designs and usability of plazas. It established three categories of spaces: open air concourse, sidewalk widening, and the urban plaza. Similar to that of the 1961 plazas, providing these spaces generated bonuses in high density office districts. However, the bonuses were no longer allowed as-of-right, and instead, pursuant to a certification by the Chairperson of Department of City Planning Chairperson to the Department of Buildings. This ensured that spaces met the newly established design standards.

Learning from the lack of usability of 1961 as-of-right plazas, the design standards for urban plazas required owners to provide amenities typically found in public parks, such as seating, planting, trees, lighting, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) access, and signage. It also required the plaza to be substantially open to the sidewalk; to be more or less at the level of the adjacent sidewalk; and for the owner to post a performance bond to ensure proper maintenance. Open air cafes and kiosks were introduced, while uninviting elements such as driveways and exhaust vents were prohibited.

Forty urban plazas were built under these regulations, which remained in effect until replaced by the public plaza design standards in 2007.

In 1977, these urban plaza standards were adapted for high-density residential districts, establishing yet another type of POPS: the residential plaza. The bonuses generated by residential plazas was similar to the 1961 plazas, in ratios and that they were first allowed as-of-right. However, beginning in 1996, they required a certification by the Chairperson of the City Planning Commission to the Department of Buildings, to ensure that the design standards have been met. Sixty-two residential plazas were constructed under these regulations, which remained in effect until replaced by the public plaza design standards in 2007.

Incremental changes to POPS regulations took place through the 1980s and 1990s, related to special districts, particularly Special Midtown District, and with the eventual elimination of some POPS categories.

By the late 1990s, an impressive amount of public space had been created in many busy areas of the City that had little open space. However, it was clear that the lack of detailed requirements for amenities in the older POPS zoning regulations meant that these spaces were significantly underutilized, and in some case were not easily accessible and even perceived as public. For those reasons, the types of POPS permitted and their locations were restricted in the late 1990s. Most notably, the bonus for as-of-right plazas was eliminated in 1996.

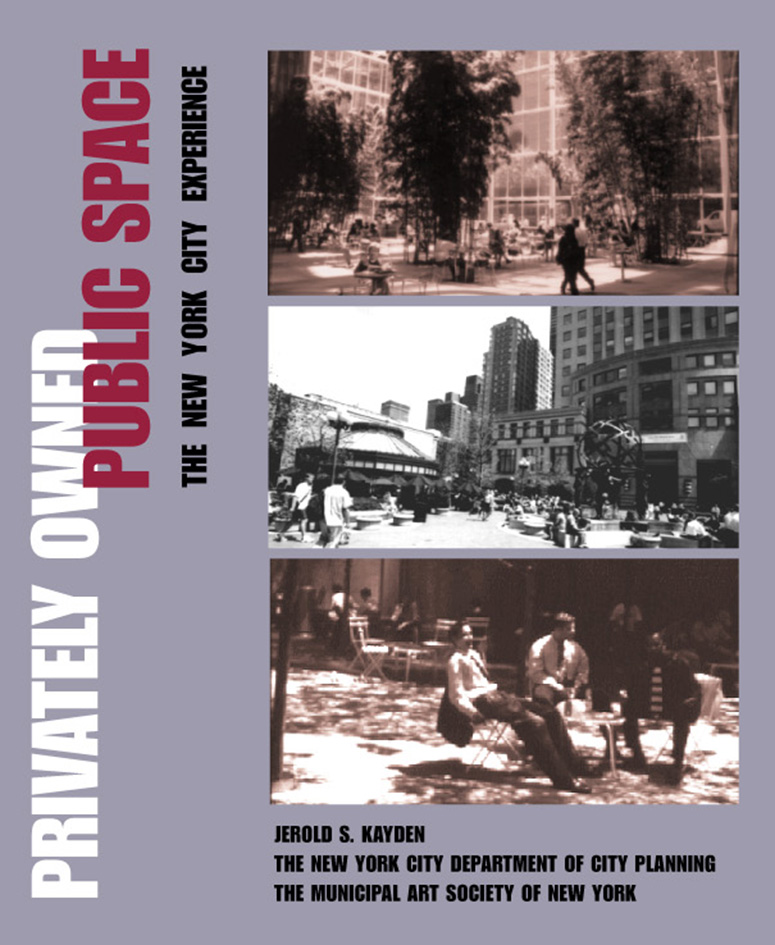

Starting in the late 1990s, Harvard professor Jerold S. Kayden, the Department of City Planning, and the Municipal Art Society (MAS) joined forces to conduct a comprehensive analysis of New York City POPS and jointly developed an electronic database with detailed information about each POPS. Based on this work and published in 2000, "Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience," describes the evolution of incentive zoning in New York City from 1961-2000, and profiles 503 public spaces at 320 buildings that had been granted additional floor area or related waivers in exchange for providing these spaces. A qualitative analysis of these spaces found that some POPS were well used, serving as destinations or neighborhood gathering spaces, while others were primarily for circulation purposes or of minimal usability.

This initial POPS database served as the basis for the Department’s current database, on which it maintains all POPS data, and which is critical to the Department meeting its obligations to report on the data and make it publicly available. The Department would like to give special thanks to Jerold Kayden and MAS for their financial support and ongoing contributions to the collection and dissemination of information about POPS, and for their advocacy work, overall.

Based on comprehensive survey completed for the book and further field studies of privately owned public spaces, the Department gained expertise in understanding the qualities and regulations that help create successful public spaces. For example, an analysis of past plaza regulations revealed that, while the introduction of residential and urban plaza standards and gradual refinement of these guidelines had improved the quality of plazas, there were still numerous instances of plazas that lacked basic amenities or included design features that inhibited public use and enjoyment. These types of issues were, at least partially, attributable to lack of specific design guidelines or outdated criteria within the zoning text. Additionally, it became clear that the more successful plazas had certain key elements in common, in particular lots of seating, attractive planting, easy, open and comfortable access, and a pleasant variety of spaces.

With all this insight, new design standards (called “public plaza” standards) were proposed by the Department and adopted by the City Council in 2007. The 2007 provisions overhauled the design regulations of prior plazas to facilitate the design and construction of high quality public spaces that, in turn, provide valuable amenities to residential neighborhoods and commercial districts. They are guided by the following design principles:

Public Plaza Design Principles

- Open and inviting at the sidewalk

- Easily seen and understood as open to the public

- Conveys openness and maintains clear sightlines through low design elements and generous paths leading into the plaza

- Provides seating and amenities adjacent to the public sidewalk

- Accessible

- Located at the same elevation as the sidewalk

- Enhances pedestrian circulation

- Safe and secure

- Contains easily accessible paths for ingress and egress

- Oriented and visually connected to the street

- Lit well within plaza and on sidewalks connecting to plaza

- Comfortable and engaging

- Promotes use and comfort by providing essential amenities

- Accommodates both small groups and individuals with a variety of well-designed, comfortable seating

- Balances open areas with greenery and trees

Learn about specific components of our design standards by referring to Zoning Resolution Section 37-70, or by seeing the “Current Standards”.

Importantly, the 2007 update introduced a process for owners to voluntarily redesign or modify their existing plaza. The public plaza standards are applied to all prior types of plazas when they come to the Department to seek a redesign. This ensures that plazas of prior standards are upgraded to a higher quality, in line with our current standards.

In 2009, the Department proposed and the City Council adopted a follow-up text amendment that further fine-tuned particular standards from 2007, particularly related to enhancing pedestrian circulation and visibility into and across a plaza.

Our current standards, when applied to older plazas that are upgraded or to new spaces, have resulted in highly attractive and usable spaces for New Yorkers, commuters, and visitors all to enjoy, providing greenery and an inviting place to sit, relax, people watch, eat, meet others – in other words, to partake and enjoy in urban life in one the world’s great cities.